The one-time pin-up girl of women’s golf has found a fulfilling post-career life in Tampa Bay.

Here she comes, walking from the clubhouse to the practice green, schlepping a mammoth golf bag emblazoned with “Jan Stephenson.” The men milling around the green, where lights and camera await, gesture toward her, offer to help, but they’re too late. Jan Stephenson waves them off. She’s more than capable of carrying her own bag.

In the ’70s and ’80s, Stephenson was one of the most successful, famous and, yes, notorious, players in women’s golf. She gave the LPGA tour a dose of sex appeal, helping dramatically increase its popularity. Now 67, Stephenson still exudes star power and swagger, balanced by an unpretentiousness and ease that make her eminently approachable.

We’ve met on her home turf of Tarpon Woods Golf Club in Palm Harbor, a faded public course that she and her partners, Michael and Diane Vandiver, are working to restore while keeping it open. The troika own the club under the aegis of their nonprofit, Jan Stephenson’s Crossroads Foundation, which provides golf-centric therapy for wounded veterans. Their trusty aide and greeter, Eddie, a lovable Gordon setter, is always nearby.

While Stephenson has retired from professional golf save for select women’s senior golf events, she’s anything but idle. Besides working to resuscitate Tarpon Woods, her packed schedule includes promotional appearances and charity events. She’s heavily involved in the wine and rum brands that bear her name, and has an interest in 500 acres of vineyard in Central California.

“There’s not a lot of women in the [alcohol] business,” she says. “It’s not for the faint of heart. It took a while, but we turned the corner two years ago and now we’re doing very well.”

All the activity doesn’t allow much time on the course. “I don’t play social golf,” Stephenson says flatly. Occasionally, she enters a local amateur event to satisfy her unflagging competitive spirit. “I can only play to win,” she adds.

Stephenson’s one-time status as golf’s pin-up girl tends to overshadow her on-the-course accomplishments. In a pro career that began in her native Australia, took off in America as the LPGA Rookie of the Year in ’74, and lasted into the 2000s, she amassed 20 professional victories, including 16 on the LPGA Tour. She won three major tournaments in the early ’80s, including the U.S. Women’s Open and the LPGA Tour Championship. In June, Stephenson will be enshrined in the World Golf Hall of Fame’s class of 2019. She admits that it matters. “It means a lot,” she says. “I got resigned to the idea that I might not get in until I died, when people would feel bad.”

As Stephenson tells it, a year after being named Rookie of the Year, she was summoned to meet with the new LPGA commissioner, Ray Volpe. He was adamant that women’s golf needed to embrace the sex-sells ethos of the era, and he could think of no one better to be the face (and body) of that push than the voluptuous Australian beauty.

Stephenson agreed to do her part — a part that paid off, but also took its toll. She’d routinely receive telexes asking her to fly to New York to meet with potential sponsors or do PR in another far-off city.

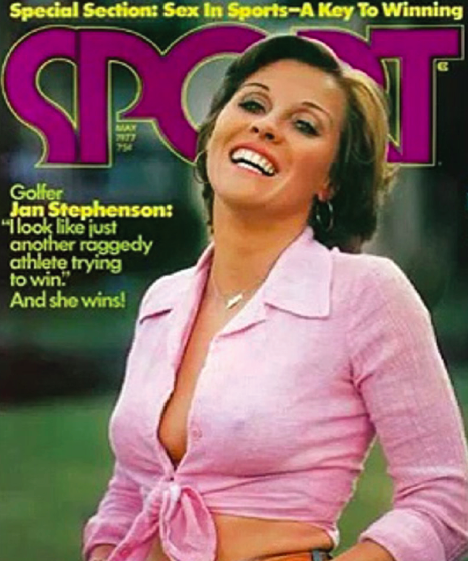

The watershed moment started with a photo shoot for a 1977 issue of Sport Magazine. During down time between a wardrobe change, Stephenson unclipped her bra and threw on a pink linen shirt. As a photographer snapped a few frames, she threw her head back and smiled good-naturedly — then forgot all about it. Soon, word came that the candid photo, racy for the time, would be the magazine’s cover.

Stephenson wrote a letter asking the editor to use a different picture. The magazine responded: too late; it’s already gone to press. Forty-four years later, sitting in the cramped, cluttered office of Tarpon Woods, she arches an eyebrow, as if to say, “Yeah, right.” The May 1977 “Sex in Sports” issue of the magazine caused quite a stir, mostly because of the Stephenson pic.

If she could take a mulligan, I ask her, would she make the same request to quash the cover? “Good question,” she says, then pauses. “There’s no doubt that it really raised my profile, and I benefited from that.” But the level of stardom that ensued, combined with her promotional commitments on behalf of the tour, sucked time and energy away from working on her golf game. “I guess I have mixed feelings about it,” she continues. “I didn’t reach my full potential as a player. But there’s no question it was fun being a superstar. I’ll always miss that part.”

Stephenson later appeared in another notorious photo that featured her in a bathtub filled with golfballs that barely covered her private parts. Playboy and Hustler came calling, but she turned them down.

In 1975 and ’76, Stephenson dated a flamboyant New York real estate developer named Donald Trump. At one point, she declined his offer to fly her to Paris for dinner because she had a pro-am tournament the next day. Trump married his first wife, Ivana, the following year.

Most of the women on the LPGA tour disapproved of the Aussie interloper’s fame and comparative wealth, whether it was due to envy or a genuine feeling that she was compromising the game’s integrity. A few players criticized her publicly — one called her a “walking soap opera” — but worse, Stephenson says, was being ostracized by her fellow tour competitors. “I got so I would steer clear of the locker room.”

Meanwhile, Stephenson began raking in the money. Through the rest of the ’70s and well into the ’80s, she would compete in tournaments through Sunday, and often fly out that night for a whirlwind promotional appearance on Monday that included meet-and-greets, photos, dinners, speaking engagements and a round of golf. By Tuesday, she was off to another tour event. Stephenson missed practice rounds, and recalls being constantly exhausted. But those appearances brought in $15,000 per, she says.

“It’s easy now to say I shouldn’t have done it,” Stephenson reflects. “It was hurting my game. But how do you turn that down? When I showed up at a tournament, I’d already earned second-place money.”

Stephenson says her best years were 1982 and 1987, when — between product sponsorship deals, promo appearances and winnings — she made $700,000 to $800,000.

In ’87, Stephenson, then ranked No.1 in the world, was leading the S&H Classic in St. Petersburg by five strokes going into the final round. As she drove back to her hotel that Saturday night, a girl ran a red light and crashed into her car, sending her to the hospital with a back injury and broken ribs. Stephenson dropped out of the event, then returned to action too quickly, playing with a wrap around her ribs. “I was playing an exhibition round with Jack Nicklaus and he made me promise to take some time off and heal,” she recalls.

The St. Pete crash was among several freak injuries and mishaps. During one tournament, a pine needle fell from the sky and punctured Stephenson’s ear drum. In 1990, she was mugged in Miami and suffered a severe fracture of her finger that forced her to miss several months on the tour.

In 2000, with her LPGA career winding down, Stephenson joined forces with three other tour veterans to found the LPGA Senior Women’s Tour, which three years later was rechristened The Legends Tour. Stephenson won the inaugural event, followed by several others.

This year’s Senior LPGA Championship features a prize fund of $600,000, while the purse for the Women’s PGA Championship totals $3.85 million. It’s not a stretch to say that Jan Stephenson played a significant role in the steady drive toward lucrative prize money in women’s golf.

Has the scorn she received in prior years given way to gratitude? “Some of the women of my era, and even those who came after, have acknowledged that I had an influence,” Stephenson says. “I don’t hear from the younger players, but that’s OK — we run in different circles.”

Six years ago, Stephenson moved from Orlando to New Port Richey, where she lives by herself in what she describes as a typical neighborhood. She doesn’t miss the frantic pace of fame, nor the craziness that accompanied it, but neither is she cut out for the quiet life. “I can do without the chaos,” she says, “but I do like the action. I guess I’d like to be a bigger fish in a smaller pond around here.”