What’s Italian for FOMO?

There is always the fear at a big international art fair — especially the 2019 Venice Biennale, themed “May You Live In Interesting Times” — that you will miss out on seeing the art that is the most Interesting of all.

It’s so easy to become engrossed in a single piece that you lose track of the time and suddenly whoa, there’s a whole nother venue to consider (there are two main Biennale venues, Arsenale and Giardini, both at the southeastern end of the city), and a globe’s worth of international pavilions, plus special exhibitions all over Venice. But your back is killing you and the Arsenale’s about to close for the day and… well, there’s always tomorrow.

But that’s one goal of going to see art, no? That a painting or an object or a room will be so overwhelmingly… Interesting, that you won’t want to move on to something else.

So, in that spirit, here are 13 things I saw on my first day at the Biennale that were so interesting that they stopped me from moving on.

A note on “Interesting”: The curator of this year’s Biennale, the American critic and gallerist Ralph Rugoff, emphasizes that his chosen theme is layered with irony. For one thing, the familiar phrase is not, as most of us assume, an “ancient Chinese curse” but an “ersatz cultural relic” made up in the West and thus, says Rugoff, a useful fulcrum for thought in the era of fake news — not just a curse but a challenge. Judging from the works assembled in the sprawling Arsenale complex, the artists of this Biennale believe we’re living in Distressing/Dystopian/Very Very Complicated Times, cursed with facing the consequences of racial tension, media saturation, political unrest and environmental threat. Or at least that’s the takeaway from “Proposition A,” the collective label for the works in the Arsenale. We’ll see today whether the works grouped in the Giardini as “Proposition B” — many of them by the same artists in A, but in different media — suggest a similar conclusion.

Zanele Muholi

A black lesbian South African artist who incorporates props, makeup and costumes into self-portraits that confront stereotypes with in-your-face audacity (and not a little humor), Muholi is a presence throughout “Proposition A” in the Arsenale.

Jesse Darling

Besides being visually arresting, this gathering of red primary school chairs on spindly legs invites contradictory interpretations. To us, it suggested that achievement, or even just the opportunity to go to school, is out of reach for many in the world. The wall card described the chairs as standing tall together, albeit unsteadily, “with an air of celebration and defiance.” Perhaps both interpretations can co-exist.

Michael Armitage

Instantly riveting in its capture of violent action in the moment, Armitage’s painting takes on added layers of meaning when you read the description: It was inspired by “staged campaigns of political agitation” that the artist witnessed as a photojournalist covering the lead-up to general elections in Kenya in 2017.

Nicole Eisenman

Eisenman’s sculptured heads grip the attention, like an accident you can’t turn away from — oversized, powerful, grotesque, but still painfully human.

Liu Wei

Microbes exploded into macro size? You could see that in this piece by the Chinese artist Liu Wei — or just stand in awe at the sheer shiny beauty of huge aluminum shapes encased in a giant glass box.

Alexandra Bircken

In a show with many chilling images, this was perhaps the most disturbing: 40 black latex figures, suspended from ladders that extend high above the viewer to the ceiling. Inevitably suggesting lynching, it might also, as the wall card suggests, be a portrayal of the human condition — striving, falling, climbing again.

Julie Mehretu

Among the rare pieces in “Proposition A” that did not overtly contend with social issues (though her work has been known to subtly incorporate details from politically charged photographs), Julie Mehretu’s paintings at the Arsenale are engrossing regardless of subtext — just a furiously beautiful mess of squiggles and slashes on a barely perceptible grid.

Anthea Hamilton

It’s possible to be at once exhilarated and discomfited by Anthea Hamilton’s charged installation: exhilarated by the shock of color and theatricality, discomfited by the implications, among them the fact that the “family” tartan she uses in the piece — the “Hamilton” — was, like other tartans, a marketing tool invented to appeal to Victorian Brits and Americans, and that the Hamilton surname originates in Jamaica. Cultural appropriation, anyone?

Carol Bove (foreground) and Suki Seokyeong (background)

I loved encountering Carol Bove’s crumpled, twisted “collage sculptures” of painted stainless steel — reminiscent of John Chamberlain’s crushed metal conglomerations but more graceful, musical even. This photo also includes, in the background, a partial view of another favorite, “Land Sand Strand” by the South Korean artist Suki Seokyeong — a deceptively unassuming multi-media arrangement that marries Korean musical notation, hand-woven mats and other objects to suggest a new kind of relationship between the individual and society.

Shilpa Gupta: “For, in your tongue, I cannot fit,” 2017-18 (excerpt)

I could have stayed in this installation for hours. On sheets of paper impaled on iron rods, Gupta has inscribed excerpts from the works of 100 poets who have been imprisoned for their work or political positions. As we read, we hear the words coming in waves of multiple languages from 100 microphones, suspended noose-like above our heads.

Sun Yuan and Peng Yu: “Dear,” 2015 (excerpt)

The whoosh and snap of this installation was audible — and ominous — long before you came upon it. And then… wow. It’s as if some vicious snake has been trapped in a plexiglas cage, attached to an empty throne reminiscent of the seat in the Lincoln Memorial. (Political analogies welcome.) The snake — a length of rubber hose, to be exact — lies dormant, until suddenly it begins to whip about its cage, scraping the plexiglas with such force that you see, and hear, the marks, and then it just stops, limp again. (Please excuse my attempt midway through the video to get the whole picture by going horizontal; a no-no in iPhone video land, as you know.)

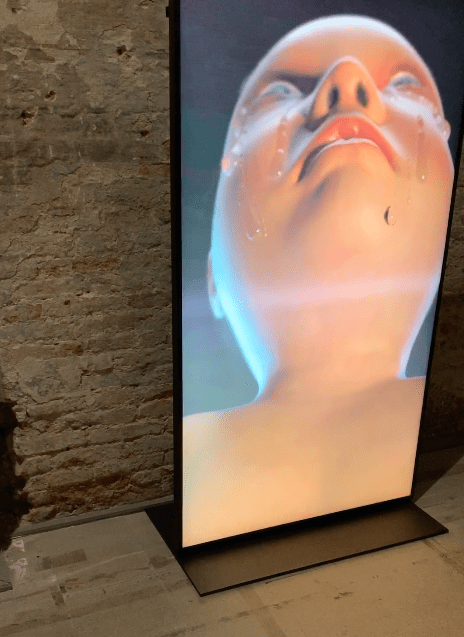

Ed Atkins: “Old Food,” 2017-19 (video still)

Not since Ally McBeal has a CGI baby given so many viewers the creeps. And that baby (above) is not the only humanoid weeping viscous tears in this installation, which also includes video “ads” for hilariously impossible sandwiches, empty opera costumes and a soundscape that insinuates itself into your subconscious. But given that it’s not advisable to take video of video installations, I can show you little more than this.

And alas, I’m not even going to be able to include photos from some of the other video installations I admired. I wasn’t able to get decent images of Kaari Upson’s eerie domestic nightmare “There Is No Such Thing As Outside,” and I wasn’t able to stay for all of Alex Da Corte’s mischievous mashup of Mr. Rogers, the Devil and phallic symbols, “Rubber Pencil Devil.” As for “Endodrome,” the much-vaunted VR installation by Dominique Gonzales-Foerster, I just wasn’t willing to wait in line.

So yes, FOMO does sometimes have to take second place to FOTO (Fear Of Tiring Out).

I already know, for instance, that I will not be attempting a visit to two of the buzziest events at the fair: The Lithuanian Pavilion’s “Sun & Sea: Marina” at the Arsenale and Swiss-Icelandic artist Christoph Büchel’s “Barca Nostra (Our Boat)” on the island of Giudecca.

“Sun & Sea,” winner of the Golden Lion prize for Best National Participation, is a performance art/opera piece in which onlookers watch a beach from above as the cast of 13 sunbathes and sings, oblivious to the signs of environmental doom. I’m not going because it requires at least a two-hour wait in line, press credential or no press credential.

“Barca Nostra” is Büchel’s controversial appropriation of the hull of the fishing boat that sank off the coast of Libya in 2015, taking with it close to a thousand migrants; only 28 survived. Büchel calls his installation a “a monument to contemporary immigration”; critics have called it everything from “mawkish” to “horrifying.” I’m not going — not because of the controversy, but because, well, it’s on the island of Giudecca and that means a ferry ride I don’t have time for. (FOTO again.)

Meanwhile, outside the Biennale…

One nautical phenomenon I was able to catch: the world’s largest sailing yacht, the “White Pearl,” owned by Russian billionaire industrialist Andrey Melnichenko and anchored near the Giardini yesterday until a tugboat came to guide it out of the lagoon. I don’t know: Is it more offensive for an artist to set up a memorial to the hundreds of desperate people who lost their lives trying to flee violence and poverty — or for a single Russian fat cat to spend $600 million on a boat so that he can be the biggest, fattest cat of them all?

And later on, way beyond the Biennale…

We finished our day with something that threatened to be cheesy but turned out to be charming: a performance of Vivaldi by a masked and be-wigged chamber orchestra in an ancient church, accompanied by a ballerina. Apparently Vivaldi concerts are a dime (a Euro? a Lira?) a dozen in Venice, and according to Trip Advisor (we found out later) this one wasn’t ranked among the best. So yes, the music wasn’t perfect, and the costumes (particularly the men’s) were a little Grandma’s-robe, and the choreography was a bit literal (holding a basket of grapes for Fall, a basket of snowy fluffballs for Winter, that sort of thing). But the ballerina was lithe and lovely, the first violinist was very adept, and for a while you could imagine that you were spending your evening just as members of the ducal set would have done centuries ago: sitting in a musty room like this, listening to musicians dressed like this, and thinking, “Hmmm, this Vivaldi fellow really has a way with a tune.”

And… One More Biennale Photo Because I Liked It: