This story is featured in duPont REGISTRY Tampa Bay’s Spring 2020 issue, “The Great Outdoors.” The digital edition is available now, and print magazines will be arriving soon in select mailboxes and distribution points around Tampa Bay.

Editor’s Note: The City of St. Petersburg is monitoring the effects of COVID-19. As of March 18, the summer schedule at Boyd Hill Nature Preserve’s Pioneer Camp was still going on as planned, but that may change as the outbreak and subsequent school closings unfold.

Every Friday afternoon during the summer, gaggles of sweaty kids ages 7 to tween line up outside a barn nestled among the oaks and pines that shroud South St. Petersburg’s Pinellas Pioneer Settlement at Boyd Hill Nature Preserve. Four at at a time, they scramble into an empty basin floating in a larger basin of water. Giddy, they sit rub-a-dub-dub-style waiting for their chance to be bathed in chocolate pudding.

Armed with aluminum cans the size of buckets, adult counselors pull out gob after gob of lumpy chocolate — the bulk variety that comes from wholesale food stores. First it’s flung; then it’s smeared. No willing participant is spared.

Sweet brown sludge drips down gangly arms and legs, heads and hat brims, streaking flushed faces like war paint. The campers hoot and holler, writhe and wriggle. Some of them beg for direct hits. Not since Augustus Gloop ravenously lapped from Willy Wonka’s chocolate river has the dessert evoked such hedonism. By the end of the afternoon, 28 pounds of pudding will be gone. (Out of consideration for parents arriving in clean minivans, counselors hose off their sticky charges when they’re done.)

The chocolate-covered ritual marks the end of yet another Pioneer Camp Jamboree, a raucous field day at which campers participate in relays, water games, shelter-building, ice cream churning and other activities that alternate between folksy and feral. Like much of the goings-on at this City of St. Pete institution, the pudding bath is an unfettered adrenaline rush and a rite of passage. Offered as part of Boyd Hill’s summer rec lineup, the 10-week program harkens back to a pre-helicopter parenting era that resonates with many Gen-X parents. The large chunks of scrappy free play and myriad bygone activities (blacksmithing, fire-building, weapon-carving, leather-stamping, dutch oven campfire cooking, etc.) evoke a sense of nostalgia and wonder in even the most squeamish parents.

“Once you get to a Jamboree you’re hooked as a parent,” says St. Pete resident Lisa Halter, whose twins, now 16, joined the camp as 4th graders before graduating to junior leaders. “You’re like, oh right, this is the kind of stuff we used to do as kids.”

Throwback camp

Halter was nervous the first time she dropped her kids off at camp. When a counselor called during the first week to let her know her son had ripped his shorts from waist to seam, she left work immediately and showed up with a new pair in hand. She walked into the old “clubhouse” — a ramshackle two-bedroom structure filled with old skulls, snakeskins and broken doors — expecting to see her son, who was not particularly outdoorsy, sitting mortified in a corner. Instead she found him running through the barn in shorts that had been entirely duct-taped.

“That’s when I knew my kids would be fine,” she says. “The counselors had handled the situation in a way that made him feel safe. It was such a great thing to experience early on.”

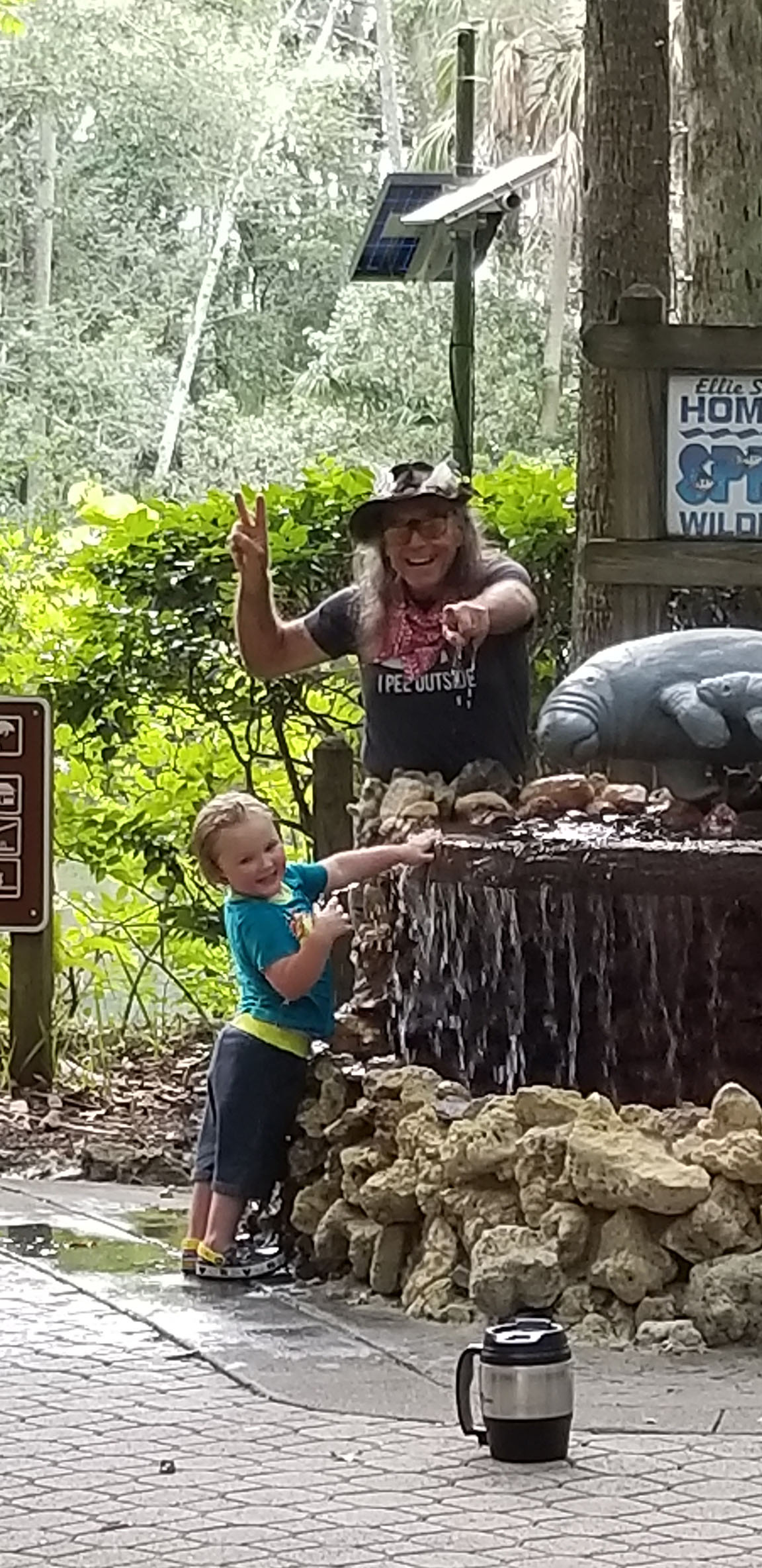

Launched in 1998, Pioneer Camp — or PioCamp as it’s known among devotees — was exactly intended to be the kind of place where kids could patch their torn clothes with duct tape. The brainchild of 66-year-old free-spirit Lynn Marshall, it was designed with what Marshall calls “a one-room schoolhouse mentality.”

His ethos was half-modeled after the youth team-building exercises and experiential learning programs facilitated by local nonprofit Pathfinder Outdoor Education, for which he worked for 11 years. The other half was a direct extension of Marshall’s childhood.

An electrician by trade, Marshall grew up in the 1960s on Pass-a-Grille Beach, where his grandparents owned The Seahorse Restaurant. Everything from the camp’s early pudding challenges to its first field trips were plucked from his youth. For example, the pudding bath began as a pudding pole inspired by the greased pole kids used to climb at Boca Ciega High School. The outings to Ted Peters Smoked Fish House were because Marshall’s grandfather used to supply the restaurant with its famous fish.

“We got kids that parents didn’t know what to do with,” Marshall says. “One mom brought us her son because he was like bouncing off the ceiling he had so much energy. We had him run around the block to burn it off. Another kid who showed up just couldn’t get along with other kids. He loved banging stuff on an anvil, so we put him in the blacksmith shop making knives.”

The first kid is now the head of IT at Tampa General Hospital. The second kid is a surgeon in Portland, Oregon. When Marshall had heart surgery earlier this year, he consulted with his former camper before going under.

“These are the kinds of kids you don’t push into a box,” says Marshall, who lives with his family on eight acres in Gibsonton. “You celebrate their differences.”

When counselor Margot Ash was a camper 16 years ago, Marshall used to keep a menagerie of farm animals on the property. Miniature ponies, goats, rabbits, chickens, an ostrich, a llama, a horse and a giant turkey were among the critters. The activity inside the clubhouse was equally curious. In one room, campers would set off mousetraps and Rube Goldberg contraptions. In another room, they’d bang on buffalo-hide drums, one of the many crafts created by campers.

“I remember someone inviting me to play outside,” says Ash, who grew up near downtown St. Pete. “It was the first time I felt myself having the agency to roam free. The other camps I’d gone to had a basketball court and a playground. At this camp, I could run through pine forests and crawl through grapevines and explore a bunker used for Civil War re-enactments. The structured time was beautiful, but the unstructured time was where we made the space feel like ours. Being given that permission was magical.”

Ash remembers the ponytailed Marshall would begin every Monday morning with a demonstration outlining camp rules and morals that involved a story about an ant that gets squashed while playing cards with his friends. To illustrate his point, he would run into the clubhouse and crash into a card table. “We definitely understood not to disturb wildlife. And we all thought he was hilarious,” she says.

Cult classic

At 23, Ash is the youngest of the camp’s four counselors. Adam Mitchell, Eric Starkweather and Nora Gaunt, all of whom work at Pathfinder during the school year, are also on staff. (Pathfinder has incidentally provided the program with all its staff members, thanks to Marshall’s ties to the organization.)

“The city has really benefited from our training,” says Starkweather, a 45-year-old Pathfinder facilitator, site director and tree-climbing trainer who was hired in 2014 as a counselor. “I would set us against any typical teacher in the county in terms of behavior management and creating a space for learning and engagement.”

Since its inception, Pioneer has remained one of St. Pete’s most sought-after summer programs. Each spring parents form a line down the sidewalk outside of Boyd Hill’s visitors center hoping to register their kids for one week — or all 10.

“It’s gotten harder and harder to get in,” Ash says. “One dad stood in line for hours. By the time he got to the desk all the spots had filled up. I honestly wish there were other camps like ours that we could point people toward.”

[Registration for summer 2020 opened at 9 a.m. on Mar. 3; by 10 a.m., all the spots in all the weeks were full.]

In order to keep the camper-to-counselor ratio at 15-to- 1, registration is capped at 45 kids per week, which is lower than the standard 25-to-1 ratio at other municipal camps. The lower ratio is exactly why Pioneer is beloved among parents whose kids struggle with emotional or behavioral issues.

Says Starkweather, “We probably have more in common with Camp Redbird [a therapeutic program offered by the City of St. Pete for kids and adults with disabilities]. We get some kids with pretty significant behavioral problems who are no longer allowed at the Y or at some other camps. We’re able to work with them, and those are the ones whose parents tell us Pioneer Camp has changed their life.”

Longtime counselor Adam Mitchell, 35, credits Pioneer’s success to its campers. When Mitchell joined the staff as a 23-year-old, he didn’t have much experience working with kids, save for the tidbits of wisdom handed down by his mother, a Pasco County guidance counselor. His chill vibe, however, and fair, no-nonsense demeanor resonated with a lot of the older campers. They felt immediately respected.

“Young people are definitely more capable than adults give them credit for,” says Mitchell, who proposed to fellow counselor Nora Gaunt last year during the final pudding bath of the summer. “The more I work with young people, the more I only want to work with young people. Their learning process is organic. I’ve learned from them how to be more open and run with ideas. It’s shaped how I interact with the world.”

He shares a story about a group of campers who cooked up batches of pine needle tea after being allowed to build a fire and boil water. Says Mitchell, “Pine needle tea has a lot of Vitamin C in it. It was used to fight scurvy back in the day.”

Lynn Marshall gets emotional whenever anyone shares a feel-good camp story. Although he stepped away from the program in 2009, he sometimes pops in on random Fridays to take in a Jamboree, always dressed in one of his wide-brimmed leather hats loaded with feathers. He says it makes his heart happy to see the counselors still guiding it by the three rules he laid out 22 years ago: take care of yourself, take care of others and take care of nature.

“The we-over-me spirit is dominant there,” Marshall says. “To see the way they interact with the kids … it makes me tear up just talking about it. Those guys get it. I couldn’t be prouder.”